How to process file uploads in Go

This article will teach you how you can upload single or multiple files to a Golang web server, and show progress reporting on file uploads

Go is a statically typed programming language which means that every value in Go is of a particular type and these types must be known at compile time so that the compiler can ensure that the program is working with the values in a safe way. This article will consider the most important built-in types in the language that you need to be aware of.

A data type specifies what a value represents and how much memory to allocate

for the value. In many cases, you don’t need to specify the data type explicitly

such as when declaring variables. It may be inferred based

on right-hand side expression. It is also possible to convert between types in

Go. For example, a float64 value may be converted to an int and vice versa.

In this tutorial, we’ll take a look at the basic types in Go that are the foundation for all other types in the language, including user created types. This investigation into data types is not exhaustive, but it will help you become more familiar with how types work in the language. We’ll also consider basic numeric operations and type conversion in Go.

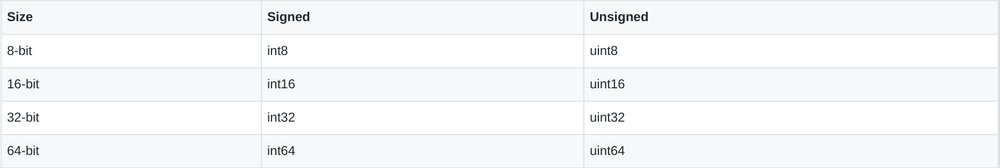

An integer is a number without a fractional component, and it may be signed or unsigned. A signed integer is one that may be positive or negative, while an unsigned integer is always positive. Go provides four distinct sizes for both types of integers which can be seen in the table below:

In addition to these, Go also provides two other types simply called int and

uint whose size may be 32 or 64 bits depending on the CPU architecture of the computer the program is running

on. That is, int or uint will be 32 bits on a 32-bit computer, and 64 bits

on a 64-bit one.

int is the most used integer type in the language and is what you should opt

for when working with integers except if you have a specific reason to use

something else. If you declare an integer variable without explicitly annotating

its type, it will be of type int.

var number = 5

fmt.Printf("The type of number is: %T", number) // The type of number is intGo does not have a specific type for characters (such as char in other

languages) so it uses the rune type to represent

Unicode character values. The rune type is an

alias for the int32 type and is equivalent in all ways.

A rune is represented using single quotes, and each one maps to a number (its Unicode codepoint) which is what actually gets stored. For example, the rune literal ‘A’ maps to the number 65. Runes can be used for any type of character in any language, not just ASCII characters. Japanese, Chinese, and Korean characters, accented letters, and even emoji are all valid rune values in Go.

var char = 'न' // a rune literal

fmt.Printf("char is %d and its type is %T\n", char, char) // char is 2344 and its type is int32

fmt.Println(char == 2344) // trueSimilar to the rune type, byte is also an alias for an integer type. In this

case, it’s uint8. The byte type is used to indicate that a value is a piece

of raw data rather than a small number and it must be explicitly annotated

unlike rune:

var char byte = 'a'

fmt.Printf("char is %d, and its type is %T\n", char, char) // char is 97, and its type is uint8In Go, a string is an immutable sequence of bytes. You can represent a string using double quotes, or back ticks (also known as back quotes) as shown below:

str := "I am a string"

str2 := `I am also a string`

fmt.Println(str, str2)String immutability means that the byte sequence that make up the string cannot be changed:

str := "I"

str[0] = "A" // cannot assign to str[0]You can of course assign a string to as many variables as you want, and even append to it while doing so. Concatenating a string does not change the original string as is observed below:

s1 := "Hi"

s2 := "Ayo"

s3 := s1 + " " + s2

fmt.Println(s1) // Hi

fmt.Println(s2) // Ayo

fmt.Println(s3) // Hi AyoThe difference between double quoted strings and strings enclosed with back

ticks is that the former does not support newlines but can contain escape

characters such as \n and

\t for example:

str := "Hello\nWorld" // \n is replaced with a newline

fmt.Println(str)Hello

WorldOn the other hand, strings enclosed with back ticks are called raw string literals. They are displayed exactly as they are written and do not support escape characters. They are often use to construct strings that span multiple lines:

str := `<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="ie=edge" />

<title>Document</title>

</head>

<body>

<script></script>

</body>

</html>.`

fmt.Println(str)<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="ie=edge" />

<title>Document</title>

</head>

<body>

<script></script>

</body>

</html>Go has two primitive types for floating-point numbers (decimal numbers). They

are float32 and float64 which are 32 bits and 64 bits in size respectively.

The default type for a floating-point number, if one is not specified, is

float64:

f1 := 3.14

fmt.Printf("Value: %g, Type: %T\n", f1, f1) // Value: 3.14, Type: float64

var f2 float32 = -0.45

fmt.Printf("Value: %g, Type: %T\n", f2, f2) // Value: -0.45, Type: float32The float64 type should be preferred in most cases because it has much better

precision that float32.

Like most languages, there are two Boolean types in Go: true and false. A

Boolean type may be annotated using bool where necessary.

t := true

var f bool = false

fmt.Println(t, f) // true falseBoolean values are also generated when using comparison operators such as ==, >, <, >=, !=, &&, || e.t.c.

b1 := true && false

b2 := 10 > 20

b3 := "Hello" == "Hello"

fmt.Println(b1, b2, b3) // false false trueAll the basic numeric operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, e.t.c. are fully supported in Go and they work on all number types:

r1 := 1 + 2

r2 := 5.4 - 1.2

r3 := 6 / 2

r4 := -0.45 * 2.34

fmt.Println(r1, r2, r3, r4) // 3 4.2 3 -1.053We also have increment (++) and decrement (—) operators, bitwise operators (

&, |, ^, <<, >>), assignment operators (+=, -=, *=, /=,

e.t.c.) and more.

a := 5

b := 5

a++ // 6

b-- // 4

c := 4 ^ 5 // 1

var d int

d += c // 1Unlike some other languages, Go does not allow implicit type conversion when performing operations on values with different types:

a := 1

b := 1.5

r := a + b // invalid operation: a + b (mismatched types int and float64)The solution is to convert between the two number types using the T(v) syntax:

a := 1

b := 1.5

r := float64(a) + b // 2.5In this article, we discussed the important data types that you’ll mostly be working with in Go, how to perform some operations and basic type conversions that you need to be aware of. We didn’t cover composite types (arrays, slices, structs) and user defined types here, but we will do so in subsequent articles in this series.

Thanks for reading, and happy coding!

Comments

Ground rules

Please keep your comments relevant to the topic, and respectful. I reserve the right to delete any comments that violate this rule. Feel free to request clarification, ask questions or submit feedback.